A little over a year before radical patriots met in a hot room in Philadelphia to ratify the Declaration of Independence, war broke out between the American Colonies and Britain at the Battle of Lexington and Concord. The “shot heard ‘round the world” in April 1775 marked a turning point for the country and the people living here, but it wasn’t the start of our independence as a nation. That ship had sailed – quite literally – more than 150 years earlier with the very first European settlers in New England.

Over the next century and a half, the people living and multiplying in the New World would combine the traditions of their homeland with an independent persistence in doing things their own way.

Settling in a new-to-them land full of nothing but possibility and being cut off via ocean from anything familiar or comfortable meant that early European Americans had to make it up as they went. The alternative was often death. From raising families and cultivating untamed land to establishing local governments and running businesses, colonists became self-sufficient out of necessity and a sense of proud ownership in the new lives they were creating.

This entrepreneurial spirit bled into everyday life.

Food was grown in farms, men and women had different but equally taxing and appreciated roles, children were cherished but given strict responsibilities, and healthcare – everything from childbirth to treatment for smallpox – happened at home, usually without any advice from someone we would comfortably call a “doctor.”

What did healthcare look like at the dawn of the American Revolution?

All across the fledgling nation, families dealt with life and death almost entirely at home. And while it’s easy to imagine that our colonial ancestors held different views and led different lives from our convenient 21st century existence, the truth is that the early American approach to both medicine and life doesn’t look altogether different from what we know and believe today.

Sure, we have flushing toilets and sterilized operating tables – both massive improvements over 18th century practices – but modern techniques and advanced technology haven’t replaced our deep-seated belief in the power of the individual.

Mothers, Doctors and Lay Healers (Oh My)

Medical care started at home in colonial America. If you were a mother in 1776, you likely had a store of homemade remedies on hand, your herb garden probably overflowed with plants used in ointments and tea, and you knew what to do for a cough or cold because that’s how it had always been done.

Whereas today’s mothers would pull out cough drops, Tylenol or that classic pink bottle of amoxicillin to treat common bugs and ailments, mothers in colonial America would have popped open their “receipt” books (recipe books) to whip up a concoction that may or may not have done any good. That is, if they had such books available and could read them. Most women of the era weren’t educated, and about half couldn’t write their own names until the end of the 18th century.

Medicine in colonial households was largely based on tradition served with a side of instinct.

Beyond everyday aches and pains, colonial households were dealing with problems that we would leave to professionals at an urgent care center. Colonial women learned how to make medicine, treat wounds and burns, and stop heavy bleeding. They also had to deal with things like measles, colic and whooping cough – diseases we can now easily prevent with vaccines.

Smallpox, yellow fever, malaria and other highly contagious and misunderstood diseases also rampaged the New World in waves. Even today’s households would struggle to stop an epidemic, and we know how contagion works. Given limited resources and low life expectancy, 18th century households expected and were often rewarded with death despite their best efforts.

If you wonder how colonial America even survived, well, a classic Jeff Goldblum quote seems appropriate: Life finds a way.

Colonists had an average lifespan of 40 to 50 years, with men outliving women by about a decade. But birth itself wasn’t usually complicated, even if a child’s chances for surviving were shockingly low. Like other types of healthcare, childbirth happened at home. And midwives made it happen.

Untrained but experienced women would deliver infants without assistance from OBGYNs – because such specialties didn’t exist as we know them now – and instead with support from women in the community. Few men practiced gynecology or obstetrics. They didn’t see the need.

But lack of specialties wasn’t the only problem in colonial American healthcare. In fact, doctors with actual medical degrees weren’t common. Of the 3,500 to 4,000 doctors practicing in the colonies at the time of the Revolution, about 10 percent had any formal medical training, and maybe half of those held degrees. It’s not much of an exaggeration to say that anyone who set up shop as a doctor could practice as one.

Quality standards didn’t exist in the colonies, and professionals weren’t required to hold a degree or go to medical school.

Given limited resources and low life expectancy, 18th century households expected and were often rewarded with death despite their best efforts.

The term “doctor” was applied liberally to everyone from lay healers – similar to modern-day homeopaths – to formally trained physicians who studied at European medical schools. The first medical school in America opened in Philadelphia in 1765, but few practitioners bothered to get a degree.

For the most part, colonial-era physicians studied via the tried-and-true method of apprenticeship. Aspiring young men who wanted to practice medicine would work under the direction of an established doctor for several years. Apprentices generally worked for free for their masters in exchange for room, board and on-the-job training.

It’s easy to see how this unregulated and non-standardized form of education could yield a host of differing opinions on disease and how to treat it. We might balk at this free-for-all approach to medical education. Early colonists did, too.

Physicians of the era were generally considered a last resort when it came to healthcare – and for good reason. Dr. Chandos Brown, Associate Professor of History at the College of William & Mary, noted in an interview via email that “a reasonably well-educated modern American knows more about the practice of medicine than the best-trained London physician of 1770.”

Euro-Americans didn’t trust doctors, at least not in the way that 21st century patients do.

And the treatments colonists could expect if they did call a doctor? Well, that depended on the doctor’s training – which, again, was limited at best – and his philosophy on diseases and cures. By and large, colonial physicians still subscribed to the so-called “heroic” approach to medicine. Hint: It was anything but a lifesaver.

Colonial Ailments & “Heroic” Medicine

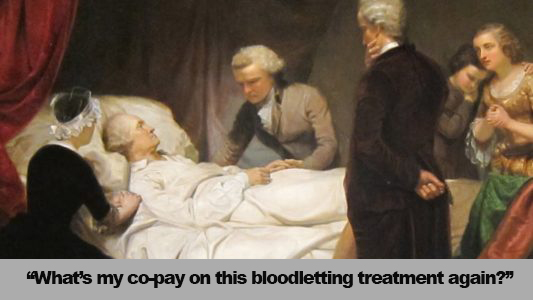

One common misconception about George Washington was that he died from excess bloodletting, a common medical treatment in the 18th century. But the nation’s first president likely died from asphyxiation due to a complication from an unchecked bacterial throat infection (epiglottitis). The bloodletting didn’t help, though. In fact, it probably made his symptoms and prospects worse.

Unfortunately for colonial Americans, bloodletting was not uncommon thanks to a belief in “heroic” medicine. Named after its intended effect – “big and bold” – heroic medicine was based on a simple, if flawed, idea: The body was imbalanced, and it needed to be purged.

Colonial patients and their doctors had no concept of germ theory, of how and why diseases happen and spread. Physicians of the era conflated the symptoms of disease for the disease itself, so corresponding cures were an attempt to address those symptoms without any attention paid to underlying causes. This could and often did have disastrous effects.

If you were lucky, you suffered from anemia and dehydration but recovered anyway. If you weren’t, you died.

Heroic medicine involved purging the body of fluids: bloodletting, leeching, vomiting, blistering and sweating. Bloodletting, the process of draining your blood using leeches or tools, such as a lancet, was especially common, with doctors using it as a first line of defense against things like inflammation.

It’s no wonder that colonial Americans trusted in home remedies when they could. Per Dr. Brown, “That these procedures were patently unpleasant doubtless persuaded many potential patients to stay home and either recover through the ministrations of the household or to consult the doctor as a last resort.”

Diarrhea, another common but potentially deadly problem for colonials, ravaged the Continental Army during the Revolution, ranking as the number one killer for soldiers. Camping in close quarters without access to basic sanitation, like soap and running water, and eating and drinking contaminated food and water, soldiers could and did easily contract bugs that led to diarrhea, which they passed along to their peers.

The common treatment for diarrhea in 1776? Castor oil – i.e., a laxative.

Again, doctors were treating the symptoms, not the disease. Because doctors didn’t understand what was causing the problem, they treated the part they could see. And because excess diarrhea, compounded with the use of laxatives, can lead to dehydration, patients could get stuck in a vicious cycle of “treatment” that ultimately resulted in death.

Disease claimed more lives than bullets did in the Revolutionary War.

But viral illnesses didn’t stay on the battlefields. Everyday colonial life included the occasional (and deadly) outbreak of virulent diseases. Doctors had no cures for diseases like smallpox or malaria, which they grossly misunderstood. The word “malaria” literally comes from the Latin for “bad air”: Colonists, both patients and physicians, assumed that the disease was caused by noxious air. It would be another century before the real culprit was identified.

As for smallpox, a particularly savage worldwide plague, there were efforts to reduce its impact and keep outbreaks at bay, but colonial Americans didn’t exactly embrace it. “Inoculation” shares a common idea with immunization: use the disease against itself to destroy it.

The concept of inoculation (also called variolation) has existed since ancient times in certain parts of the world, but the first documented case in England happened in 1718. Physicians would take a small bit of smallpox matter and insert it under the skin of a healthy patient, forcing the body to develop antibodies to the disease. Eighteenth-century doctors might not have understood the physiology behind why inoculation worked, but they recognized the results.

Early adopters and promoters of inoculation included Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin and other founding fathers and prominent figures.

But not everyone was on board with the admittedly risky and expensive procedure. Like today’s anti-vaccination movement, inoculation naysayers didn’t trust in the science behind it. Variolation was so controversial, in fact, that doctors who promoted it got death threats – and in one case, anti-inoculation zealots bombed one doctor’s house.

And it wasn’t just the layfolk who objected to inoculation. The clergy, who also doubled as family physicians in some communities, generally rejected the idea because they felt that it went against God’s will. Established physicians also dismissed the procedure as “dangerous and medically unproven.”

Unlike today’s anti-vax movement, early colonists had reason to doubt this new approach to preventing smallpox. One to five people out of a 100 died from inoculation.

Even worse, poor people were left even more vulnerable to the disease than their affluent neighbors. Wealthy patients who got inoculated didn’t bother to stay away from public places while they were still contagious – the incubation period for smallpox can last for two weeks – which means they could infect the poorer populations around them.

There isn’t space here to list all the common ailments that disrupted colonial America life. The point is to emphasize how little 18th century physicians understood the conditions they were treating. That’s not to say that they weren’t trying or took their roles lightly. But medicine as a consolidated and regulated profession was still a century away.

In the meantime, colonial Americans resigned themselves to relatively short lives full of diseases. As Dr. Brown put it so succinctly, the 18th century “was quite literally a ‘world of hurt.’”

A Pound of Gold or a Pound of Pork?

There was no such thing as EMTALA, the federal law that requires most hospitals to treat people regardless of ability to pay, in 1776. If you needed care that your mother couldn’t provide, you either had to pay for it or you didn’t get it.

Of course, that mentality would have varied by physician. There were likely doctors who worked charity cases and absorbed the cost themselves or charged wealthier patients extra to make up the difference – not unlike modern hospitals do with patients covered by employer plans.

But by and large, formally trained doctors of the era set prices “by their own costs, their style of living and, quite naturally, by their own ambitions.”

And for colonials, cost presented a different set of challenges. If you think that medical pricing makes no sense today, it’s nothing compared to a time when doctors could charge what they liked without worrying about regulations or losing customers.

For the most part, European-trained physicians in colonial America catered to the wealthy because affluent colonists could afford the care. Doctors weren’t esteemed as they are today, and while they might have ranked slightly higher in social standing, it wasn’t by much. To make up the cost of getting a medical degree, colonial doctors tended to treat wealthy families.

Though few, if any, rules existed for the practice of medicine in colonial America, among the first regulations was a resolution to limit overcharging for medical services. In Virginia, one fee schedule that took effect in 1736 lasted for at least two years, but additional measures to control fees were defeated in 1748, 1761 and 1762. Even at the outset, America struggled with the cost of care.

Part of the reason that men started entering the obstetrical field was money. Since most colonial births were normal, physicians realized the potential for another income stream. Wealthier women, swayed by the European medical degrees of well-to-do physicians, started the trend of using obstetricians instead of midwives.

As today, medical care from professionals cost a lot of money in the 18th century. Considering that the treatments of the day often failed to actually treat or cure any condition, the price tag seems even more shocking.

Case in point: One wealthy colonist paid Dr. John Minson Galt a little over £27 for “thirteen days’ attendance for smallpox” in 1792. That’s about $4,100 in today’s American currency.

To say that Euro-Americans had no concept of health insurance wouldn’t be entirely true. While what we would consider health insurance didn’t exist, at least a few versions of private prepaid care and government-sponsored funds for medical care did.

The United States Marine Hospital, created by law in 1798, established a fund to pay for the care of disabled seamen. Sailors would pay 20 cents out of their monthly earnings for hospital care, a process administered by their employers. Funds were collected by the U.S. Treasury on a quarterly basis and distributed in the district from which the funds came. The government picked up the tab for the bulk of the cost of care.

This early safety net for sailors wasn’t common, but it does illustrate that the federal government and its founding fathers had some concept of providing care for people who wouldn’t otherwise be able to afford it as early as the founding of the United States itself.

And at least one example exists of a private physician setting up something akin to health insurance but what was closer to our modern-day “concierge plans.”

Dr. William Shippen, Jr., of Philadelphia, set up a system in which his patients could pay a set price on an annual basis for routine care. In one case, he charged a patient 15 guineas – about $1,935 in today’s currency – per year for general advice and attendance. This would have been a hard rate to keep up even for the wealthy.

Still, the colonies’ ever-expanding professional class, made up of merchants, lawyers, bakers and shopkeepers, among others, could afford to pay in cash, so they did.

For people who couldn’t pay in cash or gold, doctors would accept bartered goods and services in exchange for medical care. Common goods included tea, coffee, linens, foodstuffs and housewares. Dr. Shippen sometimes accepted unusual goods for services on a whim, such as a “bad painting” or a lottery ticket.

Payment was discretionary in colonial America, meaning what was charged for services and what was accepted wholly depended on the physician and family involved.

Poor people and slaves were at the mercy of goodwill. In the case of slaves, colonial masters tended to cover their care since it was seen as taking care of property – maintaining the “investment,” so to speak. In one horrific example, a 1775 legal record recounts the case of a slaveowner who charged a man with raping and impregnating one of his slaves, named Rose. The plaintiff wasn’t so much concerned with Rose’s physical and emotional wellbeing as he was the “damage” that had been done to his “property.” In other words, he was more upset about the loss of labor for nine months.

For the poor, novel options might have existed. One “man-midwife,” as male obstetricians were called in this era, used indigent women as practice for medical students learning about midwifery. These women, unable to pay for care otherwise, agreed to allow students to attend their deliveries in exchange for professional midwife services.

Medical treatments weren’t the only cost that colonists had to contend with. Early pharmaceuticals, largely based on herbs and natural elements, weren’t cheap since many of the ingredients were imported from overseas.

In the third edition of a popular domestic medical guide, Every Man his own Doctor (1736), the author advises would-be drug makers to avoid what he calls “ransacking the universe” for “outlandish Drugs, which must waste and decay in a long voyage.”

It is meaningless to ask, in some ways, about “access to health care in the 18th-century.” There simply was no such thing to which one might have access. – Dr. Chandos Brown

Colonial apothecaries stocked plants and herbs from places like Turkey, Russia, Egypt, Persia, Arabia and England – not easy to get or keep in an era that required lengthy travel times but had inadequate preservation techniques. Colonists might have brewed up their own potions at home, but doctors preferred to use heroic measures over medicinal treatment. One exception was the use of opium to alleviate pain, something that hasn’t changed in the last two centuries.

Healthcare 243 Years Later

When asked about 18th century colonial Americans’ access to healthcare, Dr. Brown of the College of William & Mary noted that it’s “meaningless to ask, in some ways, about ‘access to health care in the 18th-century.’ There simply was no such thing to which one might have access. What we share with them, I think, is the need to maintain an illusion.”

Americans today are more aware of what we should be doing, even if we don’t always do it. We know that picking up a stomach bug from the church potluck doesn’t spell our doom. It will pass in a few days with fluids and a good Netflix binge.

Broken bones don’t usually lead to amputations, and diarrhea can usually be treated with a few doses of OTC meds. Vaccines for measles, whooping cough, diphtheria, smallpox and other infectious diseases are now readily available in the U.S. even to those who can’t afford them. In fact, smallpox, once a significant threat to the globe, was considered eradicated worldwide in 1980.

Dozens of websites exist proffering medical advice to anyone who wants it, many of these sites run by official sources, like the Mayo Clinic or the National Institutes of Health. Notwithstanding the increasing obesity rate and scary stats about cancer, heart disease and other deadly illnesses, Americans today generally live about twice as long as our colonial forebears.

“Medicine has advanced at a pace that would have beggared the imagination of even the most visionary physicians of the 18th-century,” noted Dr. Brown.

Yet not quite 250 years after the American Revolution, our attitudes about healthcare haven’t altogether changed despite incredible access and high quality standards. We still prefer the DIY approach to medicine whenever possible while recognizing the skill and expertise of specialists for conditions like cancer or birth defects.

We might gape in wonder at a practice that literally drained the blood from a person’s body – a person who was already unwell – but colonial Americans needed to feel like they were doing something about disease, even if they didn’t understand it. Today’s alternative therapies and experimental clinical trials aren’t a far cry from that mentality, the need to do something in the face of incompetence.

Medicine, as all science does, exists on a continuum of study and revision. Bloodletting sounds and was horrible, but it and other heroic treatments were based on the prevailing medical theories of the day. Two hundred years from now, historians might wonder at some of our practices, too.

The Pursuit

Theories about the future of medicine aside, there is one concrete idea that hasn’t changed in over two centuries: cost.

In the 21st century, we complain about the high cost of medical care, for good reason. Even people with health insurance face difficult choices on how to pay for care. Something as basic as an MRI can cost a few hundred dollars or thousands depending on where you get it done. We’re no strangers to the crippling cost of healthcare in America in 2019.

Our Declaration of Independence asserted that every person has the right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, but this egalitarian ideal is more theory than practice.

Programs like Medicaid, established in 1965, attempt to address the shortcomings of poverty by offering coverage to people who can’t afford it. The Affordable Care Act, signed into law nearly a decade ago, sought to give people health insurance but didn’t do much to address the underlying problems, primarily cost. New attempts to address this issue, such as the much-discussed but misnamed “Medicare for all” approach, will also fail if they don’t dig into the root of the problem.

And that root is that medical care remains as expensive, in many ways, as it was in 1776.

Advanced technology, pharmaceuticals, the insurance industry, the entire healthcare system that we know today – plus the fact that we live longer and need more (and costlier) medical care with age, not to mention a hundred other factors – all work together to make healthcare even more unattainable to people with limited resources.

Make no mistake: We’ve come a long way since the days when just about anyone with the right tools could bleed you to death in the name of medicine.

For people with the means to pay for it, medical care is bursting at the seams with possibilities in the 21st century. For those earning barely enough to cover the cost of everyday life, all the fabulous cures of this golden age might as well be fiction.

Make no mistake: We’ve come a long way since the days when just about anyone with the right tools could bleed you to death in the name of medicine. Surgeons do more than pull teeth and set bones. Pharmacists, the modern-day apothecaries, go to school and learn the chemistry behind the pills we take, which can treat everything from headaches to thyroid deficiencies. Physicians spend years immersed in intensive medical training. We have beautiful hospitals with effective equipment and a vast array of medical knowledge at the tap of a button.

And, perhaps most important but least appreciated, we know how germs work, and we wash our hands. Good hygiene alone has likely saved millions of lives in the last two centuries.

But medical advancements, technology and education aside, our collective American attitude about medicine and healthcare hasn’t evolved as drastically as our approach. Surrounded by doctors and hospital systems – even in rural areas, thanks to telemedicine – and bolstered by medical information available online, American patients still retain the inherent individualism that founded the country.

That extends, to some degree, to our feelings about who should pay for healthcare.

Is it a commodity or a right? Does medical care being a right preclude its value as a commodity? In other words, if all men (and women) are guaranteed life as an inalienable right – and by extension, healthcare would support the ability to live – then how do we address the fact that in 2019, millions of Americans forgo not only health insurance but medical care in the name of cost?

These are larger questions than this article wants to answer. What started out as a fun project to see what healthcare looked like in 1776 turned into a deeper dive into the history of American healthcare than I realized when I started writing it. But these are the questions that need answering in the 21st century. If America hopes to guarantee those inalienable rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, then healthcare reform demands more than passive attention from its people.

Non-web resources used in this article:

1 Starr, Paul. The Social Transformation of American Medicine: The Rise of a Sovereign Profession & the Making of a Vast Industry. Updated Edition. New York: Basic Books. 1982.

2 Family and Work in Revolutionary America. New Dimension Media. 2007. Accessed via Amazon Prime Video, June 2019.

3 Abrams, Jeanne E. Revolutionary Medicine: The Founding Fathers and Mothers in Sickness and in Health. New York: New York UP. 2013.

4 Cotner, Sharon, et. al (Eds.). Physick: The Professional Practice of Medicine in Williamsburg, Virginia, 1740-1775. Colonial Williamsburg: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. 2003.

5 Email interview with Dr. Chandos M. Brown, Associate Professor of History at the College of William & Mary. June 2019.